Safeguarding Seals: Threats & Conservation

By Emma Marriott, Conservation Assistant

Seals are among Scotland’s most iconic coastal species. Historically, they were also some of the most heavily persecuted. Seen as a pest and a threat to fish stocks, the populations of both grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) and harbour seals (Phoca vitulina vitulina) were being squeezed towards local extinction by unrestricted hunting in the early part of the 20th century. Since then, the importance of seals as integral parts of our marine ecosystems and as conservators of coastal productivity has become better known, inspiring ongoing efforts to protect them.

Since the first piece of legislation was put in place to protect them in 1970, the UK now hosts 40% of the worldwide population of grey seals. However, harbour seals are still struggling. In the 20 years prior to the 2016 seal counts, the North Coast and Orkney populations (where there once dwelt the largest populations of harbour seals in the UK) saw declines of 85%. And, whilst it’s true that grey seals are a success story in the making, they are nevertheless one of the rarest species of seal worldwide.

_Jamie_McDermaid.jpg)

What drives seal declines?

Seals face many threats, some of which are entirely natural. In Scotland, the most common of these include predation (by orcas or “killer whales”, which are in fact dolphins!), disease, and the availability and distribution of their prey. Yet the majority of pressures that seal populations face are now driven by human activity:

Pollution

Marine pollution appears in many forms and its effects can be just as numerous.

- Oil spills can remove the waterproofing from a seal’s fur, making them more susceptible to the cold and affecting how well they can swim and catch their prey.

- Raw sewage, industrial waste and agricultural runoff (chemicals and excess nutrients from farmland) can impact productivity within marine food chains, resulting in less primary producers (such as phytoplankton) and therefore fewer fish. Chemicals can build up within a seal’s blubber, passed onto them through the food that they eat or even from mother to pup.

- When ingested, marine litter like plastics or fishhooks can cause internal blockages that could be life threatening, and entanglement in fishing line or other looped items can cause serious injury or trap seals underwater, where they will drown.

Habitat Loss

Seals regularly emerge from the water, sometimes for days at a time. They do this to socialise, moult, rest, digest the day’s meals and to replenish their body’s oxygen supplies. They require undisturbed areas of land to feel safe. The steady expansion of businesses, buildings and recreational activities onto coastal fringes makes this habitat harder to come by, pushing them into potentially suboptimal locations and putting them at greater risk of disturbance.

Disturbance

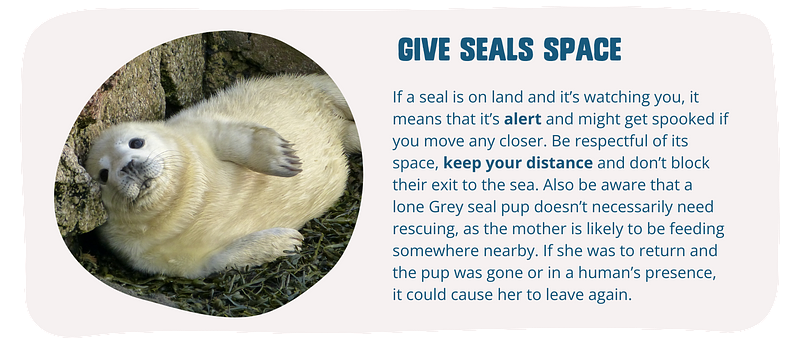

It can be tempting to approach seals. Their big, dark eyes and dog-like faces are incredibly alluring, but getting too close can cause them distress. This stress can cause seals to flee from the area, draining energy, dividing mothers from their pups, and even causing them to avoid certain locations in favour of quieter but potentially lower quality ones. This impacts their feeding and breeding success, which in turn affects their survival and that of their young.

The RSPCA recommend maintaining a distance of at least 100 metres from seals. Use binoculars or a camera with a long zoom to get a proper look at the seals without ever getting close enough to upset them.

Climate Change

- Warming oceans are pushing seal populations northwards as they follow their prey in pursuit of cooler water. Warmer currents could also spur the arrival of non-native species, which might compete for resources or carry new diseases to Scottish waters—diseases that native species have not evolved resilience to. Also, warmer water encourages the growth of toxic algal blooms, some products of which cause seals severe damage to their nervous systems.

- Extreme weather, including harsher and more frequent storms, can strip fishing nets from moorings and cast them adrift, posing serious entanglement risks. Rockfalls resulting from increased erosion can crush seals as they’re resting on land, and an increase in rough sea conditions may wash away grey seal pups before they are ready to leave the land.

- Rising sea levels are flooding low-lying haul-out sites–especially the sandy estuarine beaches preferred by harbour seals.

Why protect them?

Seals are an essential element in coastal marine ecosystems. As apex predators (at the top of their food chain) they “control” the populations of their prey. This population regulation works both ways, for if there is less prey for seals to eat then there will not be enough food to sustain an increase in seal numbers, keeping the populations in balance. We can therefore use seals as “ecological indicators” of the vitality of UK waters and of any changes to food webs, as their presence or absence is indicative of a healthy environment. Lots of seals means lots of fish, which ultimately means a healthy ecosystem.

_Emma_Marriott.png)

They also play a vital role in the recycling and dispersal of nutrients throughout the water column and between land and sea. This is an important service that increases primary productivity and thus feeds creatures from the bottom to the top of the food chain—humans included.

With females capable of producing only one pup each per year, and with half of these perishing before they reach one year old, any large impacts on seal populations could take them many years to recover from. It could therefore be very easy for these species to be nudged back to the brink in Scotland and in the whole of the UK.

What’s being done to protect them?

Following the Conservation of Seals Act 1970, which was introduced to protect vulnerable populations of harbour seals in response to localised declines, various other laws and legislation has come into effect surrounding the protection of seals in Scotland.

Of these, the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010 is the main legislation. Under this Act, five Scottish “Seal Conservation Areas” (SACs) were designated. These are on the East Coast, the Moray Firth, the Outer Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland. In an SAC it is illegal to take or kill seals without a licence, which will only be provided under specific circumstances. The Act also made it an offence to “harass” seals on designated haul-out sites, which were allocated through the Protection of Seals (Designation of Haul-Out Sites)(Scotland) Order 2014.

On paper, this protects important and vulnerable seal populations from hunting and human disturbance, but we know that the threats to seals are even more far-reaching. This is why seal conservation charities and marine organisations are taking practical measures to protect them. Charities such as British Divers Marine Life Rescue, who deal with cases of marine mammal strandings and entanglements; the Seal Research Trust, who educate people on the problems seals face and who recruit keen citizen scientists to participate in seal monitoring surveys; and the Marine Conservation Society, who campaign for better protection of the marine environment and rally communities and volunteers to clean up Britain’s beaches. The list goes on, revealing the passion that’s out there for these stunning animals and the lengths that people are taking to help them thrive.

What can we all do to help keep seals safe?

.png)

Keen to find out more?

Keep your eye on our blogs page for the next installment of this 3-part series of blogs about seals in Scotland, or read the first blog on Spotting the Difference: Seal Species in Scotland! In the next blog we will be discussing the issue of human disturbance, how it impacts seals and what we can do to minimise it.

Until then...

Check out the Grey seal and Harbour (Common) seal profiles on our Wildlife Page.

Seal Pup Rescue

Spotting seal pups on our beaches is not unusual. It is normal for a seal to spend time onshore and seal pups will often be left by their mother whilst she feeds. Seal pups face many challenges including rough weather and predators and while they will usually just be resting and regaining their strength there are some occasions when they may need help.We've created an easy to use checklist to help you decide if a pup is in need of rescue. You can download it HERE.

To keep up to date with what’s happening at the Scottish Seabird Centre throughout the year, follow us on Facebook or Twitter.

My role as Conservation Assistant has been funded by The National Lottery Heritage Fund via the New to Nature programme - an exciting initiative that is helping to support people from diverse backgrounds into environmental roles. To find out more, visit: www.groundwork.org.uk/new-to-nature-apply